Introduction

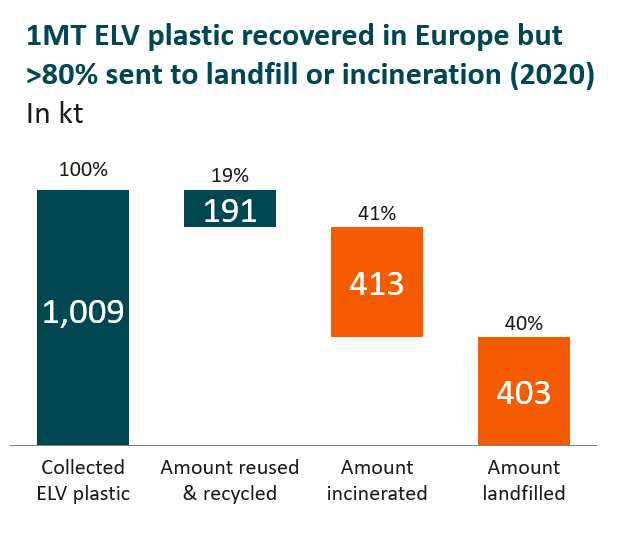

The Plastic Loop Pilot Project, encompassing initiatives like Loop Industries’ Infinite Loop™ and European automotive pilots, aims to close the recycling loop for plastics in sectors from packaging to vehicles. As global plastic waste exceeds 400 million metric tons annually [G2], these efforts promise to transform waste into valuable resources. Recent data shows a 70,000-tonne facility could save 418,600 tonnes of CO₂ yearly compared to virgin PET production [3]. However, 2025 reports reveal persistent challenges, including low recycling rates in Asia (under 20% for vehicle plastics) [5] and overlooked construction waste contributing 40% to landfill volumes in regions like Metro Vancouver [4].

Expert discussions on social media highlight polarized views: technological breakthroughs versus accusations of masking overproduction [G8]. This analysis synthesizes factual data and perspectives to assess if these pilots drive genuine change or fall short of systemic reform.

Technological Innovations Driving the Plastic Loop

Central to the Plastic Loop Pilot Project are advancements in chemical recycling and AI-enhanced processes. Loop Industries’ Generation II technology, activated in recent pilots, produces PET monomers without water and with reduced energy, enabling scalable food-grade resin [2].

A life cycle assessment confirms it slashes CO₂ emissions significantly [3]. Similarly, Porsche, BASF, and BEST’s September 2025 pilot successfully recycled automotive plastics, handling mixed streams via chemical methods [6], while BASF’s gasification of shredder residue addresses mechanically challenging wastes [7].

Emerging tools like AI and machine learning improve sorting efficiency, cutting contamination and energy use [9]. Freepoint Eco-Systems’ early 2026 PVC demo plant targets a notoriously hard-to-recycle plastic, diversifying approaches [8]. These innovations align with web analyses showing closed-loop systems recapturing 50-80% of material value [G2], with enzymatic hydrolysis offering high retention for PET [G10]. Yet, as a 2023 ACS study notes, mechanical recycling remains cheaper but less effective for complex plastics [G2].

Environmental Impacts and Sustainability Gains

Environmentally, these pilots offer substantial benefits. The Infinite Loop™ facility’s 418,600-tonne CO₂ savings underscore chemical recycling’s edge over virgin production [3]. In automotive sectors, where plastics make up 15-25% of vehicle composition, pilots like the Netherlands-Germany initiative test recycling from 100 end-of-life vehicles, boosting circularity [1].

Reuse models, such as LOOP 2025’s return of 893,000 cups via deposit machines, complement recycling by reducing waste [10].

However, impacts aren’t uniformly positive. Studies warn of microplastic emissions and high energy demands in some processes [G6], with gasification potentially emitting NOx [G9]. A 2025 systematic review emphasizes pollution from incomplete loops [G1], and X sentiment echoes concerns about “dirty” recycling that disrupts water cycles [G16]. Despite this, data from Franklin Associates [3] and MDPI analyses [G12] highlight net reductions in emissions and waste, positioning these as viable for critical sectors like electronics, where plastics form 20% of e-waste [5].

Systemic Challenges and Economic Barriers

Beyond tech, systemic hurdles persist. In Asia, GIZ studies reveal regulatory gaps and fragmented chains hindering viable recycling for high-value plastics [5]. Construction plastics, largely ignored, fuel 40% of Metro Vancouver’s landfill volume [4]. Economic critiques, per a 2024 Science article [G6], note recycling’s non-viability at scale without subsidies, with only 9% of plastics recycled globally [G5].

X discussions amplify these, with experts decrying corporate obstruction since the 1990s—e.g., killing recycling standards [G15]—and low demand for post-consumer waste [G19]. A National Geographic piece warns of an “environmental disaster” from unscalable processes [G8]. Critics argue pilots risk greenwashing, enabling “Big Plastic” to sustain production projected to double by 2050 [G3], rather than pursuing degrowth.

Social Equity and Diverse Perspectives

Perspectives vary widely. Optimists on social media praise innovations for CO₂ savings and jobs [G20], while degrowth advocates push for production cuts over endless loops [G14]. Waste pickers in the Global South face displacement without inclusion, per equity-focused trends [G17]. Balanced views from ACS [G2] and ScienceDirect [G4] suggest integrating community engagement for fair outcomes.

Critics, including a 2025 report [G1], highlight how corporate funding masks failures, with internal doubts about feasibility known for decades [G5]. Yet, constructive voices call for cross-sector collaboration, as in GIZ’s Asian frameworks [5].

Constructive Solutions and Future Pathways

Active solutions include policy reforms for producer responsibility [5] and AI-optimized sorting [9]. Pilots like LOOP 2025 demonstrate reuse’s potential [10], while BASF’s gasification scales complementary routes [7]. Emerging trends favor hybrid models: reduction plus recycling, with MIT’s low-energy methods cutting use by 80% [G9].

Proposals under study, per npj analyses [G14], advocate bans on single-use plastics and equitable value chains, potentially slashing emissions 30-40% more than recycling alone.

KEY FIGURES

- A 70,000 tonne Loop Industries Infinite Loop™ facility could save up to 418,600 tonnes of CO₂ annually compared to virgin PET production (Life Cycle Assessment by Franklin Associates) [3].

- Plastics constitute about 15–25% of a vehicle’s material composition and around 20% of total electronic waste, yet recycling rates remain critically low in these sectors, especially in Asia [5].

- Metro Vancouver construction sector plastics, largely overlooked, contribute significantly to landfill volume, with the construction sector responsible for roughly 40% of landfill volume in the region, much of it plastic packaging waste [4].

- Loop Industries Generation II technology reduces energy use considerably and eliminates water use during PET recycling, improving efficiency and scalability [2].

RECENT NEWS

- September 29, 2025: Porsche, BASF, and BEST successfully completed a chemical recycling pilot project targeting automotive plastics, advancing circularity in high-value plastic waste streams [6].

- October 2025: BASF and BEST GmbH conducted a gasification pilot project for recycling automotive shredder residue, a challenging plastic waste fraction [7].

- Early 2026: Freepoint Eco-Systems plans to commission a U.S. demo plant for scalable PVC chemical recycling, aiming to address a traditionally difficult-to-recycle plastic type [8].

- April 2025: LOOP 2025 project reported nearly 893,000 returned reusable cups via public deposit machines, demonstrating promising results in reuse systems for packaging [10].

- Ongoing: The Automotive Plastics Circularity Pilot in the Netherlands and Germany is testing dismantling, sorting, and recycling of plastics from 100 end-of-life vehicles to optimize closed-loop recycling networks [1].

STUDIES AND REPORTS

- Franklin Associates (2025): Life Cycle Assessment of Loop Industries Infinite Loop™ PET shows significant CO₂ emission reductions compared to virgin PET, supporting claims of environmental benefits from chemical recycling technology [3].

- GIZ India/China with German BMZ (2025): Study on Circular Pathways for High-Value Plastics from ELVs and e-waste emphasizes the need for cross-sector collaboration and regulatory frameworks to enable economically viable recycling in Asia, highlighting systemic barriers beyond technology [5].

- ETH study (2025): Examined gasification of automotive shredder residue as a complementary chemical recycling route, focusing on waste streams difficult to recycle mechanically, showing potential but requiring further scale-up [7].

- Light House Construction Plastics Initiative (2025): Analysis of plastic waste from construction in Metro Vancouver reveals the sector’s plastic waste is largely unaddressed, proposing circular economy interventions to reduce landfill dependence [4].

TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- Loop Industries Generation II Technology: Produces PET monomers (DMT and MEG) from waste PET without water use and with reduced energy demand, enabling continuous production of food-grade recycled PET resin at scale [2].

- AI and Machine Learning: Emerging tools improving plastic sorting efficiency and quality, reducing contamination and energy use in recycling streams, thus potentially enhancing pilot project outcomes [9].

- Chemical Recycling Pilot Projects: Porsche/BASF/BEST’s completion of chemical recycling pilots for automotive plastics and BASF/BEST’s gasification approach demonstrate advances in handling mixed and difficult plastics, moving beyond mechanical recycling limits [6][7].

- PVC Recycling Demo Plant: Freepoint Eco-Systems’ upcoming chemical recycling facility aims to scale recycling of PVC, a challenging plastic type, indicating diversification of plastic recycling technologies [8].

- Public Reuse Systems: LOOP 2025’s reusable packaging collection via automated deposit machines shows viability of reuse models complementing recycling in reducing plastic waste [10].

MAIN SOURCES

-

- https://globalimpactcoalition.com/automotive-plastics-circularity-pilot-launched/ – Automotive plastics circularity pilot in Europe

- https://www.waste360.com/fleet-technology/loop-industries-activates-generation-ii-technology – Loop Industries Generation II PET recycling technology

- https://greenstocknews.com/news/nasdaq/loop/loop-industries-executes-a-multi-year-offtake-agreement-with-nike-the-global-leader-in-athletic-footwear-and-apparel – Life cycle assessment of Loop PET and corporate partnerships

- https://www.recyclingproductnews.com/article/43666/pilot-program-confronts-constructions-plastic-problem – Light House’s construction plastics circular economy pilot

- https://wrf2025.org/accelerating-circularity-high-value-plastics-recycling-in-automotive-and-electronics/ – Circular pathways for plastics in automotive and electronics sectors in Asia

- https://newsroom.porsche.com/en_AU/2025/sustainability/porsche-basf-best-pilot-project-chemical-recycling-40692.html – Porsche/BASF chemical recycling pilot completion

- https://www.basf.com/global/en/media/news-releases/2025/10/p-25-223 – BASF/BEST gasification pilot project for automotive shredder residue

- https://www.vinylinfo.org/pressroom/breakthrough-u-s-demo-plant-advances-scalable-pvc-recycling/ – Freepoint Eco-Systems PVC recycling demo plant

- https://www.plasticreimagined.org/articles/how-ai-and-machine-learning-are-improving-plastic-recycling – AI and machine learning improving recycling

- https://circular.kk.dk/news/loop-2025-reuse-return-systems-for-packaging-in-public-spaces – LOOP 2025 reusable packaging return system results

—

Synthesis: The Plastic Loop Pilot Project and related initiatives, such as Loop Industries’ Generation II technology and the Automotive Plastics Circularity Pilot, represent significant technological advances aimed at closing the plastic loop through chemical recycling and improved sorting. These projects demonstrate potential to reduce CO₂ emissions substantially (e.g., 418,600 tonnes per year for a 70,000 tonne PET facility) and enable recycling of plastics traditionally difficult to process, such as automotive shredder residue and PVC.

However, multiple recent studies and pilot findings highlight systemic challenges beyond technology, including fragmented value chains, economic viability issues, regulatory gaps, and social equity concerns, especially in rapidly developing regions like India and China. For instance, construction plastics remain largely unaddressed, contributing heavily to landfill volumes. The success of these pilots depends on integrated approaches combining collection infrastructure, policy support, and community engagement.

Critics argue that while these pilots advance recycling, they may risk greenwashing by focusing on recycling technologies without sufficiently addressing overproduction and the need for plastic use reduction (degrowth). Reuse systems like LOOP 2025 offer complementary strategies that may alleviate pressure on recycling systems.

In conclusion, the Plastic Loop Pilot Project is advancing recycling technologies and demonstrating scalable models but should be viewed as one component within a broader systemic transformation that must include reduction in plastic production and consumption, policy innovation, and social inclusivity to truly revolutionize plastic sustainability rather than mask systemic failures.