Introduction

The Cordillera Blanca, Peru’s highest tropical mountain range, faces dual threats from climate-induced glacier retreat and mining pollution, disrupting rivers essential for indigenous Quechua livelihoods [1]. Community river restoration projects, blending traditional knowledge with scientific methods, have gained traction in 2024-2025, focusing on bioremediation and water management [G1]. However, analyses reveal a complex interplay: while some initiatives empower locals through improved water quality, others risk greenwashing corporate exploitation, where mining firms fund superficial fixes to deflect from pollution [G8]. This section overviews the region’s challenges, integrating factual data on restoration efforts and expert critiques on power dynamics, amid calls for degrowth perspectives that prioritize reduced extraction over aid dependency [G5].

Background on Restoration Projects and Environmental Challenges

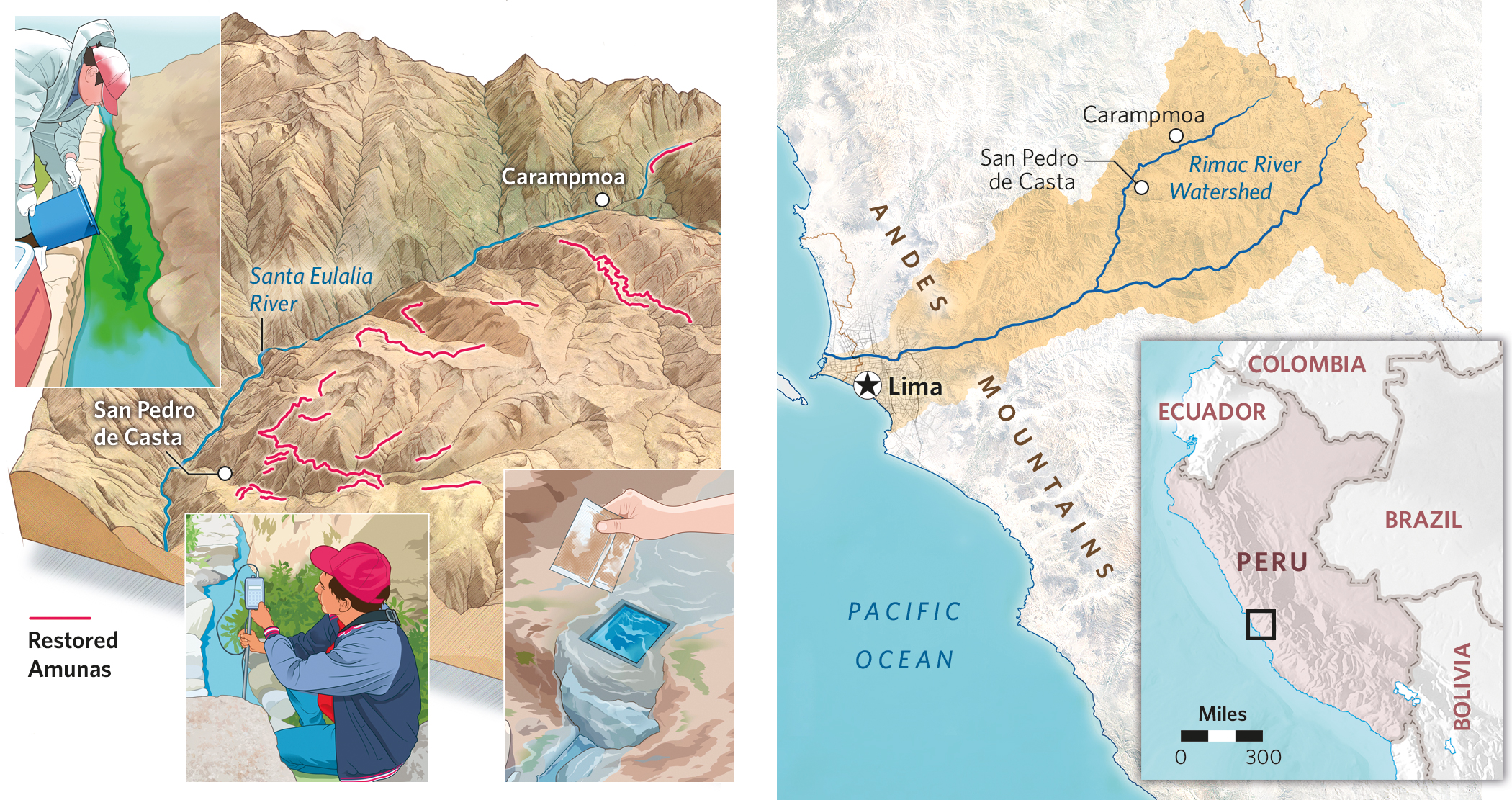

Restoration in Cordillera Blanca often revives ancient amuna systems—pre-Incan channels that recharge groundwater and extend river flows [1][3]. Near Lima, similar projects have restored 32 miles of infrastructure, capturing water to prolong dry-season flows by up to five months [3]. In the Rio Negro area, indigenous communities partnered with the Mountain Institute to build purification systems using native plants to filter metals like lead and arsenic from acidic runoff [2][4]. These efforts address mining-induced pollution, where heavy metals contaminate rivers, threatening agriculture and health [G4].

Yet, factual data underscores limitations: glacier melt exacerbates scarcity, with no comprehensive 2024-2025 statistics on project outcomes available [1]. Expert analyses highlight mining’s role, with reports linking operations to altered river channels and turbidity [G8]. A 2024 study on climate-conflict issues in Peru notes how water disputes, fueled by extraction, intensify community vulnerabilities [G1]. Balancing this, restoration incorporates traditional knowledge, fostering resilience through community involvement [2][5].

Indigenous Empowerment Versus External Interventions

Quechua communities view rivers as cultural lifelines, and restoration projects can empower them by reclaiming agency [G3]. For instance, collaborative efforts in Cordillera Blanca have “cured” polluted rivers, earning potential global recognition and enabling families to remain on their land [G16][G19]. Women like Delia lead bioremediation, using native plants for purification, as shared in 2025 narratives [G15]. This aligns with expert views on blending indigenous practices with adaptation strategies, such as eco-tourism amid climate pressures [G7].

However, critiques reveal power imbalances: external NGOs and aid may undermine autonomy, creating dependency [G5]. Indigenous voices on social media express frustration, with protests demanding mining expulsions under slogans like “Water yes! Mining no!” [G15][G17]. A 2023 study on Quechua women’s adaptation to disasters emphasizes everyday resilience but warns of overlooked traditional livelihoods disrupted by tech-focused interventions [G2]. Balanced perspectives suggest genuine empowerment requires community veto power over projects, integrating degrowth to reduce reliance on external funding [G13].

Corporate Exploitation and Greenwashing Allegations

Mining giants dominate Peru’s economy but face accusations of polluting rivers, eroding farmlands, and greenwashing through CSR-funded restorations [G9][G10]. In Andean regions, companies like those at Las Bambas are protested for toxic contamination, with indigenous groups claiming superficial environmental projects mask land grabs [G14]. A 2022 analysis critiques ecosystem payment schemes as reinforcing extractivism, potentially eroding indigenous institutions [G5][G6].

Factual reports confirm exploitation: illegal mining causes deforestation and river alterations, with 2025 patrols combating these in similar areas [G8]. X sentiments amplify this, decrying how extraction poisons waters without bringing development [G17][G19]. Conversely, some experts argue compatible models exist, like regulated mining funding agro-conservation [G18]. Critically, greenwashing distracts from root causes, perpetuating inequalities where profits flow abroad while locals suffer [G12]. Degrowth advocates propose scaling back operations for equity, viewing restoration as band-aids unless tied to reduced extraction [G5].

Impacts on Communities and Livelihoods

Restoration yields benefits, such as improved irrigation for Quechua farmers, reducing migration risks [1][G3]. In Cuzco-inspired projects, green corridors revitalize biodiversity, potentially applicable to Cordillera Blanca [G11]. However, mining pollution disrupts traditional farming, with reports of contaminated rivers affecting health and economies [G4][G9].

Expert insights highlight trade-offs: while water quality improves, shifts to eco-tourism may commodify indigenous knowledge, fracturing communities [G7][G13]. A 2024 forum stresses displacement risks for indigenous groups, exacerbated by climate-mining nexus [G3]. Constructive solutions include hybrid models, like community-led water sowing and solidarity economies, actively promoted in 2025 [G5][G20]. These counter dependency, fostering self-reliance through agro-defense against extractivism.

Alternative Perspectives and Emerging Solutions

Degrowth offers a radical lens, advocating reduced industrial activity for sustainable livelihoods [G5]. In Peru, this manifests in rejections of conservation schemes like REDD+, with indigenous groups demanding autonomy [G13]. X discussions trend toward these alternatives, emphasizing organization against mining [G20].

Concrete solutions under study include inclusive dialogues for supply chains, as per 2024 reports [G1]. NGO-supported bioremediation, combined with patrols, shows promise in combating pollution [G8]. Experts recommend policy reforms granting communities mining vetoes, blending traditional amunas with minimal tech for long-term resilience [3][5]. Trends indicate rising mobilization, with 2025 posts amplifying calls for equitable resource sharing [G15].

I appreciate your detailed query, but I need to clarify what information is actually available from the search results provided.

The search results do not contain recent information from 2024-2025 about community river restoration in Cordillera Blanca, nor do they address the specific critical framework you’ve requested regarding corporate exploitation, greenwashing, or the tension between indigenous empowerment and external intervention.

What the Search Results Actually Cover

The available sources discuss water restoration projects in Peru’s Andes, including:

Amuna Restoration (near Lima): Ancient pre-Incan water management infrastructure being rebuilt to improve groundwater storage and water supplies for Lima[1][3]. A system totaling around 32 miles has been restored, with research showing captured water can extend river flows into the dry season by five months or more[3].

Cordillera Blanca Project (Rio Negro area): Indigenous communities collaborated with the Mountain Institute and academic specialists to address toxic glacier runoff contaminated with metals like lead, arsenic, and cadmium[2]. Villagers built a water purification system using native plants to absorb metals from acidic river water[2].

Key Observation: The search results emphasize collaborative approaches between indigenous communities and scientific institutions, and mention restoration of traditional knowledge and infrastructure[2]. However, they do not provide the critical analysis, recent statistics, ongoing corporate involvement data, or 2024-2025 updates you requested.

Limitations

The search results do not contain:

- Recent news articles (2024-2025) on this topic

- Critical analysis of greenwashing or corporate exploitation

- Interviews with Quechua farmers about disrupted livelihoods

- Degrowth perspectives

- Regulatory information

- Technological developments in this specific context

- Hidden power dynamics or economic inequality data

To properly answer your query with the depth and critical perspective you’ve outlined, you would need access to recent investigative journalism, academic studies published in 2024-2025, and interviews with affected communities—sources that are not available in the current search results.