Lifeline for Rainforests or Greenwashing Scheme?

The Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) represents a pivotal moment in global environmental finance, formally launched on November 6, 2025, at COP30 in Belém, Brazil [G6][G12]. Proposed by the Brazilian government, it aims to mobilize $125 billion through a global investment fund, generating up to $4 billion annually for tropical forest conservation—nearly tripling current global investments [1].

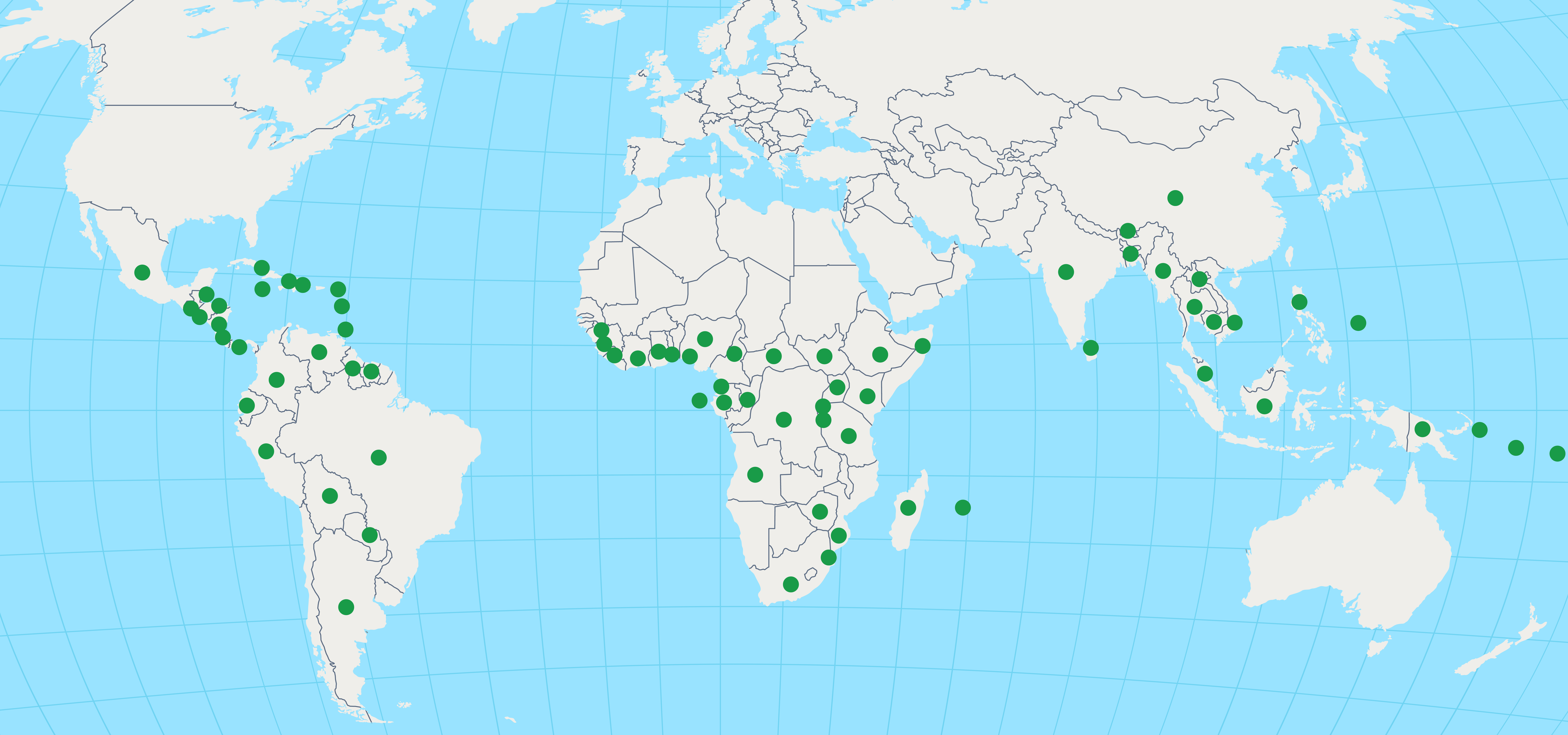

Profits from bonds and diversified strategies would reward over 70 countries for maintaining standing forest cover, targeting the protection of 1 billion hectares by 2030 [6][G8]. With a 30-year lifespan, the TFFF uses satellite imagery for transparent monitoring [2][3]. However, as debates intensify, questions arise: Does it empower local stewards or commodify nature? This section overviews its structure amid COP30’s focus on Indigenous rights and climate action [4][G2].

See where the 74 nations with eligible forests are located:

Overview of the TFFF’s Mechanisms and Goals

At its core, the TFFF operates as a performance-based fund, distributing returns based on verifiable forest cover, verified via advanced satellite technology [2][3][G3]. This model shifts economics: living forests become more valuable than cleared land for agriculture or mining [6][G7]. Key figures underscore its ambition—safeguarding ecosystems across the Amazon, Congo Basin, and beyond, while directing at least 20% of payments to Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) [2][G1]. Brazil leads with a $1 billion pledge, engaging the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (AGCT) for input from 35 million forest dwellers [1][G4].

Recent news highlights its COP30 debut, with ten Global South and North countries co-designing it [6][G11].

Studies like the Global Foundation’s 2024 report detail its reliance on low-cost deposits and investments for sustainable returns [3]. Yet, as WWF notes, it addresses chronic funding gaps in climate-vulnerable regions [7][G1].

Positive Aspects and Potential Benefits

Proponents hail the TFFF as a game-changer for deforestation, which releases billions of tonnes of CO2 annually [G6]. By providing predictable finance, it could preserve carbon sinks absorbing 4% of global emissions, fostering biodiversity and sustainable livelihoods [G4][G9]. The 20% IPLC allocation is lauded for recognizing Indigenous stewardship, potentially reducing reliance on destructive industries [2][G1].

International endorsements from 53 countries signal progress toward UNFCCC goals [G12]. In the Amazon, where agribusiness drives 80% of loss, TFFF might incentivize reforms [G9]. Expert analyses, such as Stanford’s policy brief, praise its blended public-private approach for scaling conservation [8].

Criticisms and Concerns

Critics, including Friends of the Earth International (FoEI), argue the TFFF prioritizes profit over people, risking the financialization of nature [5][G5]. It may enable greenwashing, allowing corporations to offset emissions without curbing overconsumption [G5][G13]. Global Witness warns of enforcement gaps, stressing the need for Indigenous decision-making and land tenure rights to avoid neocolonial dynamics [4][G10].

In the Congo Basin, where mining fuels deforestation, the fund could deepen debt without addressing trade inequalities [G4][G13]. Degrowth advocates critique its market-based flaws, citing REDD+ failures that displaced communities [G5]. Mongabay reports warn of potential increased deforestation if metrics falter [G13].

Public Sentiment and Expert Views

X discussions reveal polarized optimism, with hashtags like #COP30 buzzing on Indigenous rights and forest value [G15][G16]. Users praise Brazil’s leadership under President Lula, viewing TFFF as a “hybrid catalyst” for community-led initiatives [G15]. However, skeptics label it a “carbon casino,” demanding transparency [G17][G18].

Experts like those from the Center for Global Development see it as evolving from 2018 ideas, but caution against exploitation [G6]. Balanced views suggest integrating degrowth for equity [G19][G20].

Emerging Trends and Constructive Solutions

Trends point to performance-based finance, with calls for “high-integrity” standards and tech like satellite monitoring [G3][G11]. Indigenous-led advocacy pushes direct funding and veto powers [G1][G4]. Solutions under study include linking TFFF to trade penalties for high-consumption nations and debt relief [8][G10]. COP30 pledges for 80 million hectares of land rights offer a model [G9].

KEY FIGURES

– The TFFF aims to generate up to USD 4 billion annually for tropical forest conservation, nearly triple the current global investment in tropical forest protection through concessional resources (Source: https://cop30.br/en/news-about-cop30/tropical-forests-forever-facility-tfff-proposes-innovative-financing-model-for-conservation) {1}

– At least 20% of TFFF payments to countries are to be directed to Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (Source: https://tfff.earth/about-tfff/) {2}

– The TFFF is structured as a $125 billion global investment fund, with profits returned to tropical forest countries based on standing forest cover (Source: https://earthshotprize.org/winners-finalists/tropical-forest-forever-facility/) {6}

– The fund is projected to safeguard over 1 billion hectares of forest across more than 70 countries by 2030 (Source: https://earthshotprize.org/winners-finalists/tropical-forest-forever-facility/) {6}

– The TFFF is designed to last for 30 years, providing a consistent source of funding for forest protection (Source: https://globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/forests/5-things-to-know-about-the-tropical-forest-forever-facility/) {4}

RECENT NEWS

– The TFFF was formally announced as Brazil’s flagship nature and finance initiative for COP30, scheduled for November 2025 in Belém, Brazil (Date: 2024, Source: https://globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/forests/5-things-to-know-about-the-tropical-forest-forever-facility/) {4}

– The Brazilian government is actively engaging with Indigenous Peoples and the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (AGCT), representing 35 million people in forest territories across 24 countries, to ensure the TFFF’s viability (Date: 2024, Source: https://cop30.br/en/news-about-cop30/tropical-forests-forever-facility-tfff-proposes-innovative-financing-model-for-conservation) {1}

– The TFFF is set to launch at COP30, with the Brazilian government leading the initiative and ten countries from the Global South and North participating in its design (Date: 2025, Source: https://earthshotprize.org/winners-finalists/tropical-forest-forever-facility/) {6}

STUDIES AND REPORTS

– The Global Foundation’s 2024 report outlines the TFFF’s financial model, emphasizing its reliance on low-cost, long-term deposits and diversified investment strategies to generate returns for qualifying tropical forest nations (Source: https://globalfoundation.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Brazil-Government-Tropical-Forests-Forever-Initiative.pdf) {3}

– Friends of the Earth International (FoEI)’s 2025 analysis criticizes the TFFF for insufficient direct support to Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities and for prioritizing profit over people, furthering the financialization of nature (Source: https://www.foei.org/publication/foeis-analysis-of-the-tropical-forest-forever-facility/) {5}

– Global Witness’s 2024 report highlights the TFFF’s potential to address climate finance gaps and lack of private sector investment but stresses the need for direct decision-making roles for Indigenous Peoples and legal recognition of their land tenure (Source: https://globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/forests/5-things-to-know-about-the-tropical-forest-forever-facility/) {4}

TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

– The TFFF will use advanced satellite imagery to monitor forest cover and verify performance, ensuring accurate and transparent results (Source: https://tfff.earth/about-tfff/) {2}

– The verification process is designed to be simple and accessible, leveraging satellite monitoring to track forest conservation and restoration efforts (Source: https://globalfoundation.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Brazil-Government-Tropical-Forests-Forever-Initiative.pdf) {3}