Introduction

Colombia’s Amazon region, a biodiversity hotspot vital for global climate regulation, has seen fluctuating deforestation rates in recent years. Following the 2016 peace accords with FARC, deforestation spiked, with 444,000 hectares of primary forest lost from 2016-2020 [1].

However, official claims highlight progress: a 25% reduction from January to September 2025, dropping from 48,500 to 36,280 hectares [G8]. This aligns with broader trends, including a 33% drop in early 2025 [G2]. Yet, reports reveal ongoing threats, such as 88,808 hectares deforested across seven hotspots from October 2024 to March 2025, driven by illicit crops and ranching [3]. Satellite data from Global Forest Watch confirms 440,953 deforestation alerts in early November 2025, covering 5.4 thousand hectares [6]. Indigenous communities and experts warn of “displacement effects,” where enforcement in protected areas pushes activities into vulnerable territories [G4]. This section overviews these trends, integrating factual data with expert analyses to assess if reductions signal true environmental wins or hide continued exploitation [G13].

Deforestation Trends and Key Hotspots

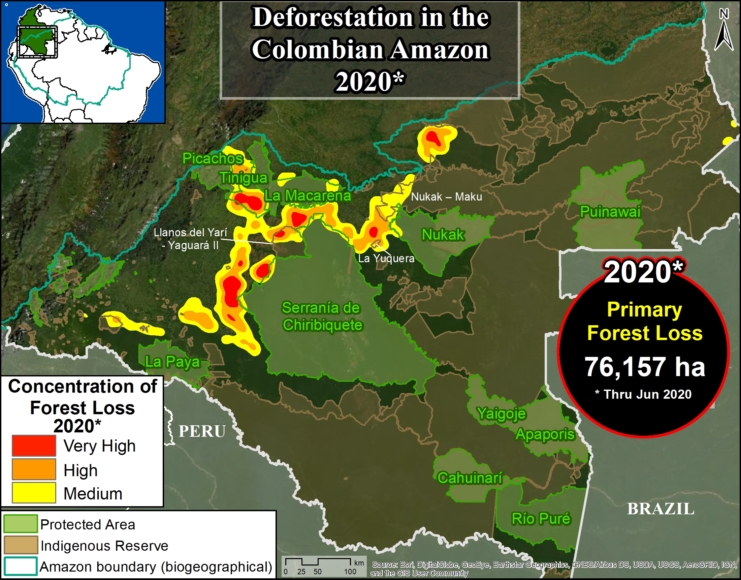

Recent figures indicate mixed progress in the Colombian Amazon. Deforestation decreased to 91,400 hectares in 2019 from a 2018 peak of 153,900 hectares, but losses persisted in protected areas, with Tinigua National Park losing 5,100 hectares and Chiribiquete 510 hectares in expanded sections in 2020 [1]. From late 2024 to early 2025, Chiribiquete saw 525 hectares cleared, while the adjacent Llanos del Yarí–Yaguará II Indigenous Reserve lost 856 hectares [2]. Overall, nearly 1.2 million hectares have been deforested in protected areas and indigenous territories over the past decade, much illegally [2].

Hotspots like Caquetá (29,706 hectares lost October 2024-March 2025) and Llanos del Yarí–northern Chiribiquete (15,755 hectares) highlight the role of 1,107 kilometers of irregular roads enabling permanent forest loss [3]. Amazonas department lost 2.9 thousand hectares in 2024, emitting 2.0 million tons of CO₂ [7]. MAAP reports note a 2024 uptick after historic lows, with 60% of national deforestation in the Amazon over the decade [2]. Posts on social media reflect public concern, with users decrying illegal roads in Chiribiquete as threats to this UNESCO site, echoing 2019-2025 sentiments about armed groups and coca cultivation.

Economic Drivers and Exploitation Challenges

Illicit economies remain key drivers, with organized crime worsening deforestation through cocaine, gold, and meat production [G10, G13]. The Guardian reports armed groups filling FARC voids, building smuggling routes and clearing for cattle ranching [G13]. Experts argue reductions may mask greenwashing, as agribusiness shifts to “legal” frontiers, with cattle ranching outpacing coca as a primary cause [G3, G15]. A SEI brief highlights policy incoherence, where deforestation goals clash with agribusiness promotion [G4].

Indigenous perspectives emphasize human rights impacts, including violence and displacement [G12]. on social media, discussions from 2024-2025 link deforestation to global demand for beef and gold, criticizing government verbiage amid Chiribiquete’s destruction [G17]. Original insights suggest a “cyclical lull,” where short-term drops follow enforcement but rebound with economic pressures [G9]. This facade perpetuates inequality, prioritizing carbon credits over local sovereignty [G7].

Technological Monitoring and Verification

Advancements in satellite imagery offer hope for verification. MAAP’s real-time tracking, partnered with FCDS since 2023, has documented 1,381 hectares lost in Chiribiquete and reserves [2]. The Amazon Observatory tracks 28,091 km of roads as of March 2024 [3], while Global Forest Watch dashboards monitor alerts like November 2025’s 440,953 [6, 8]. These tools reveal hidden deforestation under canopies, potentially underreported by 10-20% in conflict zones [G6].

However, experts note limitations: data supports reductions but misses on-ground realities, such as mining in remote areas [G1]. X posts praise high-resolution imagery for exposing burns in Chiribiquete, urging integration with AI for swift action.

Constructive Solutions and Future Perspectives

Balanced viewpoints call for alternatives like degrowth, reducing global demand for Amazon commodities [G18]. Colombia’s ban on new oil and mining in the Amazon biome (42% of territory) is a step forward [G18]. Indigenous-led governance, empowered by community monitoring, could enhance resilience [G4, G14].

Concrete solutions include expanding real-time satellite partnerships for enforcement [2] and zero-deforestation commitments, as seen in COP30 discussions [G5, G11]. WWF advocates integrating biodiversity with anti-inequality measures [G7]. on social media, 2025-2026 threads push for pan-regional protections, emphasizing local economies over exports.

KEY FIGURES

– Deforestation in Colombian Amazon decreased in 2019 to 91,400 hectares after peaking at 153,900 hectares in 2018{1}.

– 444,000 hectares of primary forest lost in Colombian Amazon from 2016-2020 following peace agreement{1}.

– Tinigua National Park lost 5,100 hectares of primary forest in 2020{1}.

– Chiribiquete National Park lost 510 hectares in expanded sections in 2020{1}.

– Nearly 1.2 million hectares deforested in Colombian Amazon protected areas and Indigenous territories over past 10 years (much likely illegal){2}.

– 525 hectares deforested in Chiribiquete National Park and 856 hectares in Llanos del Yarí–Yaguará II Indigenous Reserve from late 2024 to early 2025{2}.

– 88,808 hectares deforested across seven hotspots (Río Naya, Meta-Mapiripán, Vista Hermosa-Puerto Rico, Triple Frontera, Llanos del Yarí–northern Chiribiquete, Caquetá, Putumayo) between October 2024 and March 2025{3}.

– 1,107 kilometers of irregular roads in seven deforestation hotspots between October 2024 and March 2025{3}.

– Caquetá lost 29,706 hectares between October 2024 and March 2025{3}.

– Llanos del Yarí–northern Chiribiquete lost 15,755 hectares between October 2024 and March 2025{3}.

– 440,953 deforestation alerts in Colombia from November 2-9, 2025, covering 5.4 kha (4.0% primary forest){6}.

– Amazonas department lost 2.9 kha natural forest in 2024, equivalent to 2.0 Mt CO₂{7}.

RECENT NEWS

– New MAAP #224 report details deforestation increase in 2024 after lowest rates in over 20 years, focusing on Chiribiquete National Park and Llanos del Yarí–Yaguará II (late 2024-early 2025){2}.

– Colombia’s Inspector General’s Office reports 88,808 hectares deforested and 1,107 km illegal roads in seven Amazon hotspots October 2024-March 2025, driven by illicit crops and ranching{3}.

STUDIES AND REPORTS

– MAAP #120 (2020): Deforestation spiked post-2016 peace accord, peaked 2018, decreased 2019; 76,200 hectares through June 2020; ongoing losses in protected areas and Indigenous reserves{1}.

– MAAP #224 (2024-2025): Highlights 1,381 hectares recent deforestation in Chiribiquete and adjacent reserve amid 2024 uptick; 60% of national deforestation in Amazon over past decade; partnership with FCDS for real-time tracking{2}.

– Colombia Inspector General’s Office report (2025): Illegal roads enable permanent forest loss in hotspots; Caquetá and Llanos del Yarí–Chiribiquete among worst affected{3}.

TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

– MAAP real-time deforestation tracking via satellite imagery, partnered with FCDS since 2023 for swift action in Colombian Amazon{2}.

– Amazon Observatory of Socio-Environmental Conflicts (FCDS platform): Tracks 28,091 km roads in Colombian Amazon as of March 2024{3}.

– Global Forest Watch dashboards: Monitor deforestation alerts (e.g., 440,953 alerts Nov 2025) and tree cover loss by department (e.g., Amazonas 2024){6}{7}{8}.

MAIN SOURCES (numbered list)

1. https://www.maapprogram.org/colombian_amaz/ – MAAP #120: 2020 deforestation analysis in Colombian Amazon, trends post-peace accord, protected areas losses.

2. https://www.amazonconservation.org/new-maap-report-details-deforestation-in-protected-areas-and-indigenous-territories-of-the-colombian-amazon/ – MAAP #224: 2024-2025 deforestation in Chiribiquete and Indigenous reserve, historical Amazon losses.

3. https://news.mongabay.com/2025/07/illegal-roads-expand-in-colombias-deforestation-hotspots/ – Inspector General report on 2024-2025 hotspots, illegal roads, drivers like coca and ranching.

4. https://infoamazonia.org/en/2023/03/21/deforestation-in-the-amazon-past-present-and-future/ – RAISG and MapBiomas on Amazon-wide trends 2001-2025 scenarios, regional drivers.

5. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deforestation_of_the_Amazon_rainforest – Overview of Amazon deforestation, Colombia rate fell 66.5% by 2023 per MAAP.

6. https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/country/COL/?dashboardPrompts=eyJzaG93UHJvbXB0cyI6dHJ1ZSwicHJvbXB0c1ZpZXdlZCI6W10sInNldHRpbmdzIjp7Im9wZW4iOmZhbHNlLCJzdGVwSW5kZXgiOjAsInN0ZXBzS2V5IjoiIn0sIm9wZW4iOnRydWUsInN0ZXBzS2V5IjoiZG93bmxvYWREYXNoYm9hcmRTdGF0cyJ9&location=WyJjb3VudHJ5IiwiQ09MIl0%3D&map=eyJjZW50ZXIiOnsibGF0Ijo0Ni40MjkyNjkzNjY3MDAzLCJsbmciOjIuMjA4MzMyNTM5OTk3ODE1M30sInpvb20iOjQuOTEwNjE2MTE2MDExNTk0LCJjYW5Cb3VuZCI6dHJ1ZSwiZGF0YXNldHMiOlt7ImRhdGFzZXQiOiJwb2xpdGljYWwtYm91bmRhcmllcyIsImxheWVycyI6WyJkaXNwdXRlZC1wb2xpdGljYWwtYm91bmRhcmllcyIsInBvbGl0aWNhbC1ib3VuZGFyaWVzIl0sImJvdW5kYXJ5Ijp0cnVlLCJvcGFjaXR5IjoxLCJ2aXNpYmlsaXR5Ijp0cnVlfSx7ImRhdGFzZXQiOiJmaXJlLWFsZXJ0cy12aWlycyIsImxheWVycyI6WyJmaXJlLWFsZXJ0cy12aWlycyJdLCJvcGFjaXR5IjoxLCJ2aXNpYmlsaXR5Ijp0cnVlLCJ0aW1lbGluZVBhcmFtcyI6eyJzdGFydERhdGVBYnNvbHV0ZSI6IjIwMjItMDQtMjMiLCJlbmREYXRlQWJzb2x1dGUiOiIyMDIyLTA3LTIyIiwic3RhcnREYXRlIjoiMjAyMi0wNC0yMyIsImVuZERhdGUiOiIyMDIyLTA3LTIyIiwidHJpbUVuZERhdGUiOiIyMDIyLTA3LTIyIn19XX0%3D&showMap=true – GFW Colombia dashboard: Recent alerts (2025), tree cover stats.

7. https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/country/COL/1/ – GFW Amazonas department: 2024 forest loss details.

8. https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/country/COL/?dashboardPrompts=eyJzaG93UHJvbXB0cyI6dHJ1ZSwicHJvbXB0c1ZpZXdlZCI6WyJzaGFyZVdpZGdldCJdLCJzZXR0aW5ncyI6eyJzaG93UHJvbXB0cyI6dHJ1ZSwicHJvbXB0c1ZpZXdlZCI6W10sInNldHRpbmdzIjp7Im9wZW4iOmZhbHNlLCJzdGVwSW5kZXgiOjAsInN0ZXBzS2V5IjoiIn0sIm9wZW4iOnRydWU